It’s a little weird to call this series a dev log, because I’m far from developing anything at the moment. I’m currently working on two things;

- Kivy module Study

- Bank Account Interest Calculator Development

Before I talk about them, I’d like to point out one important thing, and that is that these logs may contain smelly/wrong programming ideas harmful for beginners. Some will definitely be some concepts I only later realize is wrong or understand it truly. These logs are made public not primarily to teach anyone, but to receive feedback from others if they happen to stumble upon my posts. Though, that is not the main function of these logs, but rather to review the things I’ve learned over the course of my self-teaching.

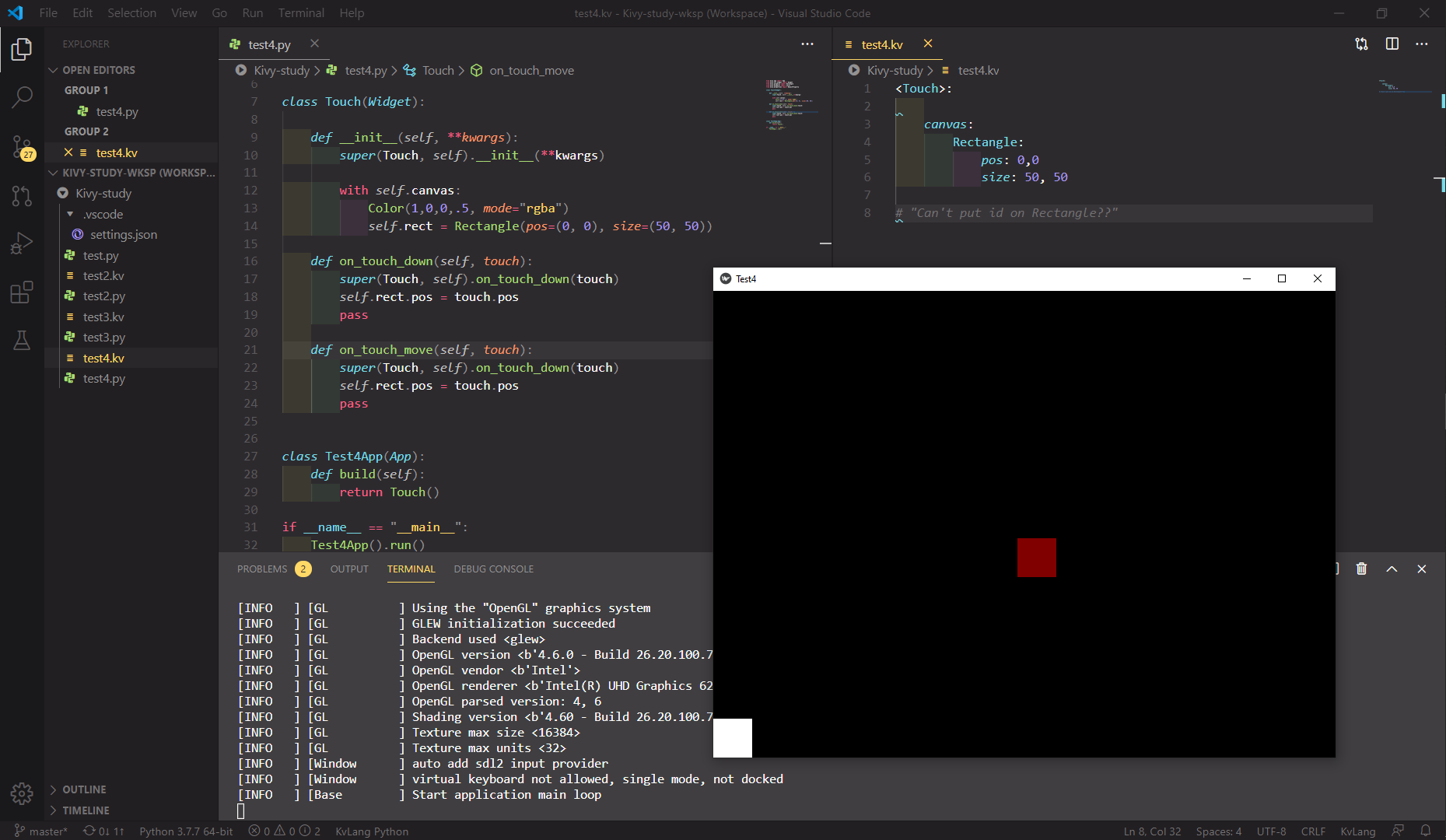

1. Kivy Module Study

After dropping Tkinter in seconds, PyQt5 in hours, and PySide2 in few days, here’s my first dev log on studying Kivy for the past few days.

I actually got further with Kivy than any other modules so far. I’m liking how it tries to be very easy to use with their .kv extension, but I’m having trouble understanding how to write anything in there. I’m currently following Tech with Tim’s Kivy Tutorials, and while it’s been amazing, it lacks in depth and doesn’t do much explanation on what goes in .kv and what goes in .py, at least as far as I have watched. I really need to learn how to read the documentations.

A notable thing I learned from this was something unrelated to the module - setattr and getattr. setattr(obj, func_or_var, value) creates obj.func_or_var = value. getattr(obj, func_or_var) calls obj.func_or_var. I found it useful in creating and calling multiple variables from a loop or conditions, like for when multiple widgets of the same type needs to be created with different names. The StackOverflow post I read said this was not recommended, and that we should use a dictionary instead. That was the whole explanation, so I couldn’t quite understand how I could use a dictionary in this situation, and moved on.

2. Bank Account Interest Calculator Development

I’ve been interested in making better financial choices lately, and that includes making the best choices in which bank I should make a transactions account in. I know that it’s pretty pointless to decide whether I pick a 0.8% or a 0.6% yearly interest rate, but if I can choose the former, of course I would.

Usually it’s easy to tell which is better by looking at their yearly interest: higher the better. But Kakao, a software company in Korea, decided it can be a little more complicated than that. They propose a 0.6% yearly interest, but paid every week. This makes a slight difference with the usual get-paid-every-year plan, because your savings increase every week, meaning your interest increase every week as well. I’m awful at maths so I might be wrong, which is another reason why I’m working on this.

Now, I have another option offered by KDB, with 0.8% yearly interest paid yearly; Nothing more. Which of the two is more profitable?

I did say I was bad at maths, but I’ve studied enough in middle school to figure out that the formula for the calculation would be:

total_cash = starting_cash * (interest_rate*pay_day/365 + 1)iterationThis was very useful at getting my answer. for KDB, I’d have to put number of years I want to calculate for (and for Kakao, the number of weeks in a year) in iteration. I didn’t wanna put an irrational number, so I decided to go for 7 years, since that should be 365 weeks.

Aaand came the result; With 1 million as total_cash, keeping money in there for 7 years would get me to 1.06 mil on Kakao, and 1.04 mil on KDB. Very easy - we didn’t even need to code. But if I stopped here, I wouldn’t be writing this, would I?

edit

It’s June 22nd and after making more progress with the project, I only now found out that the calculation above was wrong. Just note that the next paragraphs were written thinking that it was right.

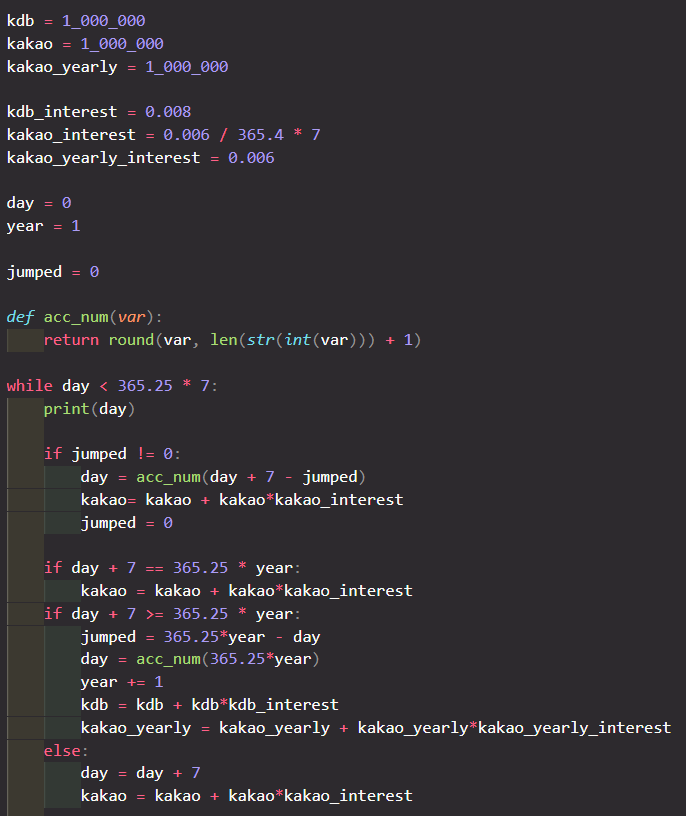

I had a new question. Obviously Kakao would get me less profit in the first few years. At what point in time does Kakao win over KDB? I could’ve done this mathematically too, but this is when I decided to write a program because I was too lazy to remember how to graph things again.

Variable kdb and kakao was used to represent the total_cash for each. I figured instead of defining a year as 365 days, I could instead have it 365.25 days to include leap years. The more specific 365.2422 days is unnecessary as I wouldn’t be calculating for more than 100 years. I had day += 0.01 on every loop, and if day % 7 == 0, kakao += kakao*(0.6*7/365), and similarly for day % 365.25 == 0. I used pyplot and plotted kdb and kakao at every 0.01 days. Here, I hit some problems.

y*10^6 = total_cash, x = year. This pic is after optimization, which I talk about below.First, the result was vastly different from what my first calculation showed. KDB actually provided more profit than Kakao, in about 4 years. I wasn’t sure why my result was different, but I figured I’d notice it as I made optimizations; Which brings me to my next point - the program ran REALLY slow, because it has to plot 73,050 points for a 10 year simulation. It was obvious that the code was inefficient from the beginning, but I left it as it is because I didn’t expect it to be so slow.

While writing the code, I noticed an extremely strange situation where day was never equal to a multiple of 7 or 365.25. I later found out that 0.05 + 0.01 != 0.06, but 0.060000000000000005. This was super weird. I was not at fault here, it was just that computers can’t give an accurate answer to such a simple calculation. At this point of time, I didn’t bother understanding the computer science behind this, and just made a function to correct the result (acc_num, as seen below).

This is the first iteration where instead of day += 0.01, I added values dynamically for day to have a value that only creates meaningful points. This took a little longer to code than I’d like to admit, trying to fix small mistakes like not realizing day + 7 == 365.25 was possible. This version was much faster, drawing 99 times less points.

But I was still getting a different result from my initial calculation, and I had no idea why. After thinking for some time, I decided to redesign the code entirely.

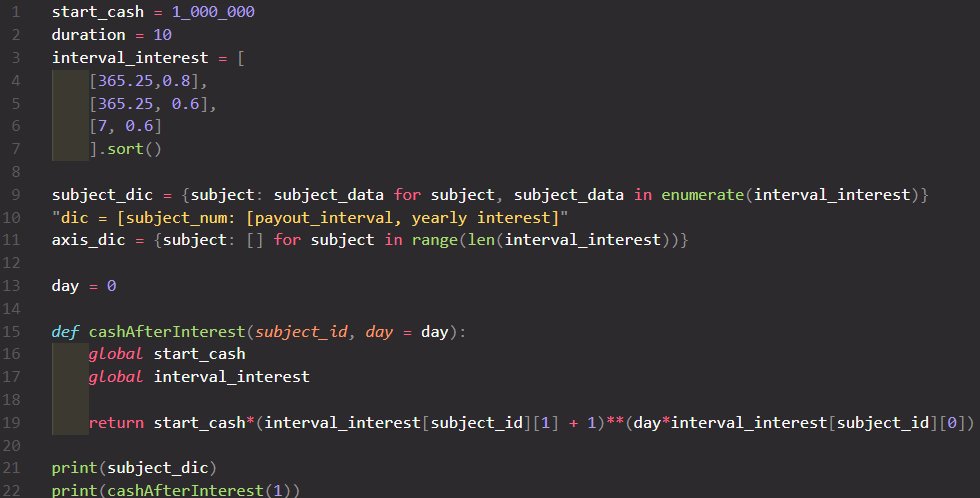

As obvious it is, I did not use the formula I presented in the beginning for the project. This was because I didn’t want to think about how I’d need to apply that in to code. After some work, though, I found out it’s not that hard at all.

I also decided to design the code to make it easier to add more ‘subjects’ to graph, and edit the yearly interest rate and the payout interval values. The first thing that came to my mind is to have a list of these values, and use setattr() in a for loop to create variables referring them. Variables’ name would be something like var{num}, so that I could call them with getattr(), and use the list to figure out the variable name. But that answer I read from StackOverflow back when I was studying Kivy stopped me. How could I use dictionaries instead?

The code above is the answer I came up with, and it was eye opening. Although not the same, this post by Ned Batchelder in 2011 helped figuring this out. Instead of referring variables, I can put the values in a dictionary and refer them with their index. This is an incredible find, because this can work as an alternative to attribute initialization in object oriented programming. As in, I don’t need to create a class to contain some values in its __init__(), but in a key’s value instead. The only problem I see is how the value is presented; It is hard to tell what exactly interval_interest[subject_id][1] means.

Summary

- I should read Kivy documentation more to understand how to make use of .py and .kv.

- I learned that

setattr(obj, func_or_var, value)createsobj.func_or_var = value, andgetattr(obj, func_or_var)callsobj.func_or_var. - 0.05 + 0.01 != 0.06. I should find out why.

- Dictionary can be very powerful in storing data without making extra variables.